Chief Operating Officer of Indelible Learning

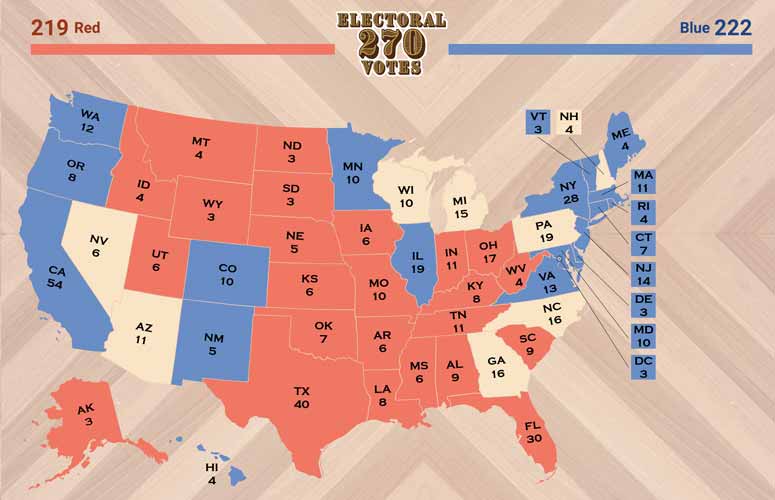

This week we updated the game map for Election Lab.

New polling shows that two states from the old map, Minnesota and Maine, are now leaning blue. Removing these states from the playable swing states on the map means now only 8 swing states remain: Nevada, Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.

A small change, but the consequences are more than we anticipated.

The first change, which we welcomed, was that Red and Blue were starting out with a closer set of initial Electoral Votes. Red now has 219, and Blue has 222 Electoral Votes. The old map had Red with 219, and Blue only 208.

But the other changes were only revealed as players tried out the new map.

If you haven’t played Election Lab before, the game pits you against an opponent for the swing states remaining on the electoral map in a presidential election. The online game we now host uses the 2024 map, which regularly updates from pre-election polls to indicate which swing states are still in play for the two campaigns.

To win these swing states, you deploy campaign resources, which represent time, people, and money. Your resources are limited. These resources are deployed in secret; neither you nor your opponent can see each other’s deployments. Finally, the resources you have placed on a swing state translate into an equal number of 6-sided dice that you will roll against your opponent’s dice. More dice means more chances of winning, but like actual elections, a lead in the polls does not translate into absolute certainty of winning.

In addition to these swing-state battles with dice, we have Event Cards. A player receives an Event Card only after losing a swing state battle. Event Cards are always good: they represent a favorable news event for your campaign, and translate into extra resources that you can deploy on the map. Event Cards are a consolation for losing, and depending on the circumstances can actually be better than the loss of the swing state itself.

With the new map, it was now harder to acquire Event Cards, because one strategy players had employed in the past was to throw the small Electoral Vote states like New Hampshire, Maine, and Nevada, in order to gain an Event Card. Now that Maine is no longer on the table, that is one fewer Event Card opportunity.

This also changed how people played for Pennsylvania. At 19 Electoral Votes, it is the largest prize on the map. But it is closely followed by Georgia (16), North Carolina (16) and Michigan (15). Does losing Pennsylvania count that much, if your campaign can compensate by using freed-up resources to win these other three states?

It depends on how you lose Pennsylvania. A sneaky strategy emerged in ELO, where players would place zero campaign resources on Pennsylvania. At first pass, this seems insane. But, if the opponent places a maximum of 5 campaign resources on Pennsylvania, they are wasted. Simply 1 resource would have been enough, if you had left Pennsylvania empty. The point of this strategy is to lure your opponent into heavily investing in Pennsylvania. If your opponent does, and you do not, you will concede Pennsylvania, but you will have up to 5 campaign resources free to deploy elsewhere (like Georgia, North Carolina, and Michigan).

Winning these 3 states, in a trade for losing Pennsylvania, would be a winning strategy. But it depends on the cooperation of your opponent. If your opponent does not invest heavily in Pennsylvania, you are down 19 Electoral Votes, without a decisive advantage in resources.

Also important is when you lose Pennsylvania. Players have also learned to use Event Cards won throughout the game to stockpile resources on big-ticket states that are still in play. But if you or your opponent plays for Pennsylvania early in the game, it is no longer on the map, and can no longer be a recipient for stockpiling. Savvy players have learned to study the opponent they are playing, to see whether it is wise to throw Pennsylvania. These players have also learned to play for Pennsylvania early, to prevent the opposing side from building up resources from Event Cards on this state.

The realists among you reading this account will object to some liberties we have taken in modeling the presidential election. First, state-by-state battles are independent statistical events in ELO, where in reality, we know that the outcomes for swing states in an actual election are correlated, especially for states of the same region. Second, in an actual election, we vote at more or less the same time. For this reason, a campaign cannot plan to decide the outcome of Pennsylvania before other states, and then use that information to plan the rest of the map.

With Event Cards, the first objection (state battles should not be independent events) is mitigated, because now the order in which you play for each swing state does matter. Players must make a series of decisions for every swing-state battle, and each Event Card, they must update their strategies.

The second objection, that voting is a single event, is not entirely true. Early voting in many states has shifted how campaigns win these votes. They will attempt to bank early votes from reliable supporters in a first wave of outreach campaigns, and return later for a second or third wave for voters who vote on Election Day.

Campaigns have another compelling reason to focus on this first wave: banking votes early for your side can be an insurance policy against late-breaking news that would be unfavorable to your candidate.

These strategies have echoes in our Election Lab game. Small changes in the electoral map mean that the successful strategies that worked a week ago must be altered. Moving from 10 to 8 swing states means fewer pathways to victory, fewer chances for a comeback late in the game, and more exposure to the vagaries of the dice rolls. The randomness introduced by the dice rolls does not mean that the state battles are pure chance: on a particular swing state, if you have a superior number of campaign resources to your opponent, your advantage—even if it is only by 1 die—is substantial.

Our alumnus, George Kaveladze, summed it up succinctly this evening: the virtue of Election Lab is its realism. The map is real, and so is the role that chance plays in otherwise closely fought swing-state battles. A 70% chance of winning means just that: 3 out of 10 times, you will lose. Likewise, the game keeps states out of reach that could not be won in real life. No matter how hard you try to invest in California, a Republican candidate will not turn this state Red. Nor will Missouri, Ohio, or Iowa turn Blue, even for the most diligent player.